Three states, three sets of priorities

Published 7:00 am Thursday, January 7, 2021

- Oregon State Capitol

When legislators in Oregon, Idaho and Washington state convene later this month, some will meet online and others will meet in their state capitol.

But the differences in the states’ priorities will go beyond how the legislatures meet in response to COVID-19 concerns. Many of the policies they set — and the laws they pass — will impact farmers and ranchers across the Pacific Northwest.

In Washington state and Oregon, both governors are Democrats and the legislatures are led by Democrats. But while cap-and trade climate policy is high on Washington Gov. Jan Inslee’s priority list, Oregon Gov. Kate Brown and legislative leaders will likely pivot toward other climate-related concerns such as renewable energy.

In the Republican-led Idaho Legislature, the top concern is what to do with a $600 million budget surplus that has accumulated since last March, when COVID-19 prompted Gov. Brad Little, also a Republican, to put the brakes on state spending.

Following is a state-by-state rundown of legislative priorities that will impact agriculture.

WASHINGTON: Governor embraces new term as ‘magic moment’

OLYMPIA — Washington Gov. Jay Inslee has taken his re-election as a mandate, calling the beginning of his third term “a magic moment of progress.”

Inslee rejects scaling back his legislative agenda because of the pandemic, which will prevent constituents from entering legislative buildings. The Democratic governor has rekindled campaigns to tax carbon and capital gains, and gradually wring some of the carbon out of gasoline and diesel sold in the state.

“We have big things to do, and I think we’re going to get them done. I’m excited about this session. I think the moment is a magic moment of progress on so many different things,” Inslee said.

The Legislature will convene Jan. 11 for a 105-day session with Democrats holding solid majorities in the House and Senate. Committee hearings will be on Zoom, and lawmakers will vote by video.

Rep. Joel Kretz, a Republican who represents northeast Washington, said getting and staying online will be a problem for him and other rural lawmakers and residents.

“We have bad internet out here, most of Eastern Washington does,” said Kretz, who plans to stay in Olympia during the session. “I have been unable to express my viewpoints fully in a number of meetings.

“The public is, the way I see it, in a really bad position for having their interests represented,” Kretz said.

Inslee said he expects legislators to largely function as they always do. “We have found remote communications has actually worked very, very well,” he said.

“I think they’re going to work out wrinkles in their process. That will take a little bit of time, but I don’t think we should trim our sails much here.”

Inslee has presented lawmakers with a two-year operating budget proposal that would increase state spending by 10.5% to $57.5 billion.

Pandemic-induced business lockdowns have not translated into a budget deficit. Inslee proposes to add to growing state revenue with approximately $1 billion in new taxes and by spending down the rainy day fund by $2 billion.

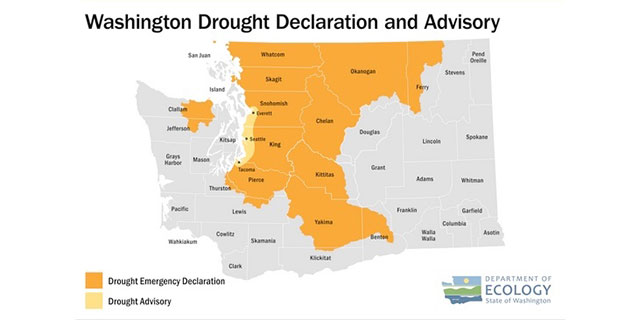

The Department of Ecology would add 62 full-time positions, including 34.6 jobs to implement a cap-and-trade plan for carbon emissions, 8.3 jobs to administer a low-carbon fuel standard and 6.9 jobs to enforce the Obama administration’s Clean Water Rule.

In outlining his agenda, Inslee said voters were given a choice, and they re-elected him to a third term by 545,177 votes. “That’s a decision that they made,” he said.

Inslee overwhelmingly captured King County, where Seattle is, by 580,352 votes, more than enough to offset the loss of 27 of the 39 counties in the state.

The governor scored his most lopsided victories in King and San Juan counties. The counties rank one and two, respectively, in per capita personal income, according to the Office of Financial Management.

On the other side of the state, the governor lost to Republican candidate Loren Culp in Ferry, Franklin and Grant counties, the three counties with the lowest per capita incomes.

Senate Minority Leader John Braun, R-Centralia, said Inslee’s proposals to raise taxes to spend “mostly on more government” were “out of touch.”

“They just don’t seem to understand how hard it is if you’re not getting that bi-weekly government check,” Braun said. “They don’t seem at all interested in connecting with people that are having a hard time getting through this.

“We have essentially a balanced budget in front of us, prior the governor’s proposal, and $2 billion in the rainy day fund,” he said. “We have everything we need to address our challenges without new taxes. It’s as simple as that.”

The state estimates a 9% tax on capital gains over $25,000 for individuals and $50,000 for joint filers would raise $975 million the first year, a figure revised downward since the governor rolled out his budget.

The tax would exempt some capital gains from selling agricultural property, but there is no blanket exemption for farmers or ranchers.

The tax, according to the governor’s office, would not apply to cattle, horses or breeding livestock sales if the property was held for more than 12 months and at least 50% of the taxpayer’s gross income was from farming or ranching.

Gains from selling a farm held for at least 10 years would be exempt, provided the taxpayer had “regular, continuous and substantial involvement” in the farm.

— Don Jenkins

OREGON: Climate conversation likely to change

SALEM — Faced with COVID-19’s persistent disruptions, Oregon lawmakers are expected to be less preoccupied with controversial climate legislation during the 2021 legislative session.

While carbon cap-and-trade legislation probably won’t hog the spotlight this year, legislators will take up other climate-related proposals during the session, which will begin Jan. 19 and end in late June.

Lawmakers are likely to concentrate on encouraging renewable energy production and adoption of electric vehicle fleets, rather than taxing fuel emissions, said Jenny Dresler, a lobbyist for the Oregon Farm Bureau.

“I think you will see a shift in the carbon conversation. I don’t think it’s necessarily going by the wayside,” Dresler said.

Cutting emissions will remain a focus for the Department of Environmental Quality and other state agencies, while the cost of new renewable energy mandates would ultimately be borne by ratepayers, she said. “It’s definitely something that should be concerning.”

Bills related to COVID-19 relief and wildfire prevention are likely to be top-of-mind at a time when the Legislature will be making difficult budget decisions amid continued economic turmoil. Gov. Kate Brown has proposed spending $100.2 billion in her overall budget for the 2021-2023 biennium, but lawmakers typically amend that amount. Of that, $24.3 billion is in the general fund, which comes from taxes. The remainder is from the federal government and other sources such as the state lottery and fees.

There will likely be pressure to raise state revenues by increasing taxes or eliminating past tax cuts, which shouldn’t be borne by small businesses, said Mary Anne Cooper, the Farm Bureau’s vice president of public policy.

State agencies such as the Department of Agriculture and Water Resources Department will also ask to raise fees for services that farmers and irrigators depend on, Cooper said. “This is not the year to be raising fees.”

Labor advocates will likely cite the pandemic’s dangers as a reason to impose or expand rules for employers, which may implicate the farm industry’s seasonal workforce, said Dresler. “Those regulations aren’t necessarily built for the little guy and our folks tend to get swept up in it.”

It’s likely that wildfire legislation will be re-introduced that would require electric utilities to develop risk-based protection plans and allow local governments to implement stricter defensible-space codes, among other measures, said Samantha Bayer, the Farm Bureau’s policy counsel.

A similar bill died during the 2020 legislative session.

Wildfire proposals will need to be thoroughly evaluated to avoid unintended consequences to rural areas, such as widespread power outages, Bayer said. Defensible-space requirements also shouldn’t require the removal of crops such as hazelnuts.

“We want to make sure that doesn’t mean conversion of productive vegetation,” she said.

Though forest management on federal lands is beyond the state government’s control, lawmakers will likely work on policies for state forestlands and fire-adapted communities, she said. “The federal management piece is important, but there are things the state can do to prepare for the next fire season.”

Exactly how productive lawmakers will be in passing bills remains an open question due to the logistical barriers of conducting legislative business remotely — at least during the early months of the session before vaccines are widely available.

Though committees have been holding hearings online during the pandemic, the proposition will be more challenging when they’re contending with the typical rush of testimony and negotiations required to meet legislative deadlines.

For farmers who live far from the Capitol, testifying on the impacts of legislation remotely will be less time-consuming than traveling to Salem, said Cooper.

On the other hand, communicating with lawmakers is much tougher when the Legislature’s business is conducted online, she said.

Farm advocates must schedule meetings rather than speaking with the lawmakers informally in the hallway, and the usual back-and-forth about policy implications is more time-consuming, Cooper said.

“It’s taking us about three times as much work to do what we do at the Capitol,” she said. “It feels like going through molasses to do the same work.”

— Mateusz Perkowski

IDAHO: Budget surplus main focus of legislators

BOISE — How best to manage Idaho’s $630 million budget surplus will be the main topic when state lawmakers convene later this month.

The surplus is more than 10 times bigger than when legislators adjourned March 19, early in the COVID-19 pandemic.

The surplus includes budget holdbacks Gov. Brad Little ordered as the pandemic swept through the state, higher-than-expected sales and income tax collections, and indirect impacts from federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act money.

The $1.25 billion from CARES helped businesses and workers pay more sales and income tax than anticipated. CARES money also went to schools and state agencies, such as the Department of Correction, which left some state general fund revenue unspent. The general fund comes from state sales and income taxes.

Little, a Republican rancher from Emmett, is scheduled to open the 2021 Legislature Jan. 11 with his State of the State address. He will include his proposed budget for Fiscal 2022, which starts July 1.

He plans a package that provides tax cuts and makes one-time investments in transportation, education and water projects.

Little’s general approach is “to get the surplus money into the economy,” state Division of Financial Management Administrator Alex Adams said.

He said Little took a similar approach to much of Idaho’s share of CARES funds, getting money “working” in the form of small-business grants, return-to-work incentives and local government assistance, among other spending.

And the governor was “surgical” in his early COVID-19 executive orders, Adams said. “For example, the construction economy continued in Idaho.” Some other states shut down construction projects, at least temporarily.

The surplus increased from $54.9 million on March 19 to $630 million in mid-December, the Legislative Services Office reported. State tax collections from July through November were 16.6% above year-earlier levels.

Little, in a June 22 memo, also called for a spending freeze among agencies next year, mandating general fund appropriations not exceed this year’s. The current general fund budget approaches $4.1 billion, including agency budget holdbacks of 5%.

About 43% of the $9.9 billion total budget is the general fund, 36% is federal money and the rest is dedicated fees. Idaho sets its budget annually.

“We are happy we are in relatively good shape but we don’t know what ‘22 is going to bring,” said Rep. Rick Youngblood, R-Nampa, co-chairman of the budget-setting Joint Finance-Appropriations Committee. “I’m cautiously optimistic for our budgeting for 2022.”

He expects legislation on using and tracking funds that come in after the session adjourns. The CARES Act infusion is an example.

The governor called a special legislative session in August to cover liability and election laws amid COVID-19 concerns, but it did not cover how to spend CARES Act funds. A committee helped guide that spending. The 16-member panel included representatives of the Legislature, state offices and agencies, small and large businesses, tribes and the state Board of Education.

Legislative leaders have also said they plan in the ‘21 session to address executive powers during emergencies.

Roger Batt, who represents several agriculture groups, said the Treasure Valley Water Users Association would like to see part of the surplus to go to more state flood-management and water-quality grants, which have strong demand and are supported by local matching funds.

Batt also expects more discussions about property-tax relief.

Hemp may also come up. The Legislature in the past has considered but did not pass bills to legalize hemp production.

Braden Jensen of the Idaho Farm Bureau said his organization “is working with legislators to see that a hemp bill is considered and introduced.”

The Legislature will meet in person. It would have to approve any changes to the session, including holding all or parts of it remotely. All official business will also be live-streamed.

— Brad Carlson