What’s your soil type? There are apps for that

Published 3:30 am Thursday, March 5, 2020

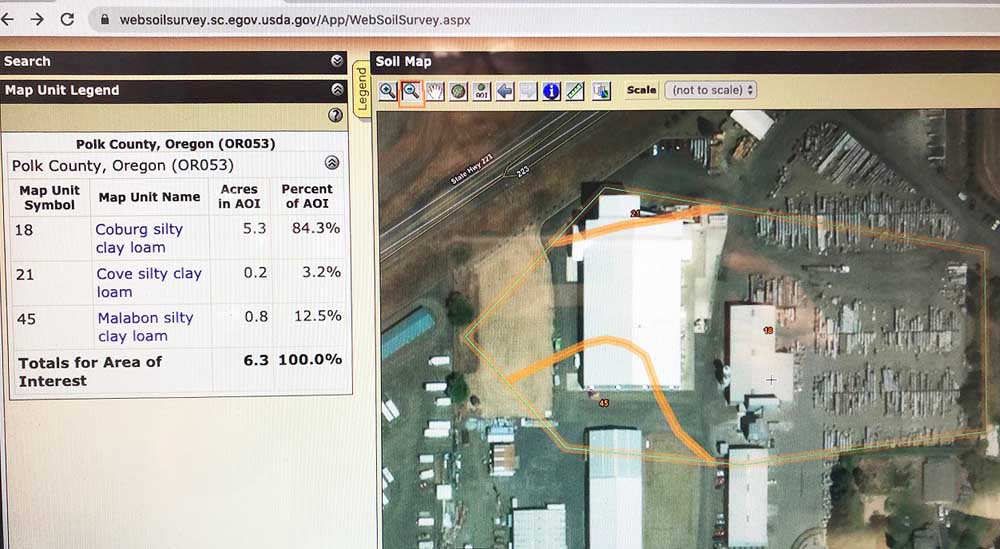

- A soil map available online.

POLK COUNTY, Ore. — Soil science has come a long way since Milton Whitney in 1899 began surveying soils in the tobacco lands of Connecticut.

Whitney’s project to match soils to crops caught on quickly. By 1927 in Oregon’s Polk County, the first maps were drawn up identifying 16 soil types in 31 units. Today, the county soil survey identifies 66 soil types in 164 map units.

“If what happened in the larger Willamette Valley is similar to the Polk example, then the number of soil series has increased by about four-fold, and the map units by five-fold,” said Andy Gallagher, a soils scientist with Red Hills Soils who was among speakers at a recent soil health workshop in West Salem. Approximately 50 farmers, growers and technicians attended the event.

For a century, soil series names were added as tests revealed differences among soils in the same classes, giving farmers a growing base of knowledge to improve practices. But before the advent of the web, that knowledge was located on paper maps that were quickly outdated, and often difficult for growers to access.

Not so anymore, said Brandon Bishop of the Marion Soil and Water Conservation District. Internet-accessible tools make it possible for growers across the U.S. to access the latest data about their soils from their smart phone, tablet or computer.

Bishop and Gallagher demonstrated two free tools for identifying general soil types from satellite and database entries. More precise details are available by physically testing one’s own soil, or by enlisting help from public and private consultants, Gallagher said.

The Web Soil Survey can be conducted from the website, http://websoilsurvey.nrsc.egov.usda.gov. At this site, users simply click on the green button to begin identifying the broad soil types of the land to be used for a farm or garden. Users type in an address, then draw a box around an area of interest on a map. Once the area is identified, the user can look up the characteristics of the plot, including soil type, drainage and permeability, recommended crops for the soil type, and much more.

Bishop demonstrated the information available by identifying the land under which the workshop took place: Chemeketa Community College’s Eola Hills Center west of Salem. By clicking on the soil map tab in that example, the app identified soil type as “Witzel, very stony silt loam,” surrounded by two other types of silty loam.

Clicking on the identification brings up several dozen descriptions of the mapped unit, from farmland classification (not prime) to drainage, flooding and irrigation properties. The offices are surrounded by Nekia silty loam, a more affable soil type for agriculture, and are planted to wine grapes.

The Web Soil Survey has its limits, as users will discover. The 28-acre scale (an average) offers general information, although official soil tests such as those taken at the Eola Hills site have added specificity to the public mapping tool.

Gallagher prefers to access soil survey information directly through the Google Earth app, because it is easy to use and provides additional information. Similar to the NRCS app, which uses Goggle maps, the user zooms in to or types the address of the area of interest. With added extensions, added contour and more specific soil type features make this app useful, Gallagher said.

In Google Earth, for example, the user can click on a “time machine” tab to see past uses of the land. For more soil and land-use details, users can download the “Soil Web Earth” extension and bring it into Google Earth, combining the features of both applications. The user can also input their land’s data, historical details, crops, photos and other observations, which may be stored for private tracking.

Using Left Coast Cellars north of Rickreall as an example, Gallagher used Google Earth’s “time machine” app to show the land morphing from a turnip field in 1995, to the vineyard it is today.

To access the app, first open or download Google Earth then add the Soil Web Earth details in the by clicking on the “Download with Google Earth” button at the Google Earth Library, www.gelib.com/soilweb.htm. Survey info is automatically entered into a button Google Earth maps. Users can click anywhere on the land to see its wide-ranging components from hydrology to summaries of organic matter and recommended crops.

Google maps features also include sunlight movement through the day across the landscape, a flight simulator, and buttons to record a tour of the property or upload photos or data, to name a few.

Rainy winter days are the perfect times to check out apps that could improve practices, Gallagher said.

“Get some of these tools and really play with them. It will give you some insight on your lands,” Gallagher said.