WAIT AND SEE: Western farmers hope to bounce back from an exceptionally dry year

Published 7:00 am Thursday, October 28, 2021

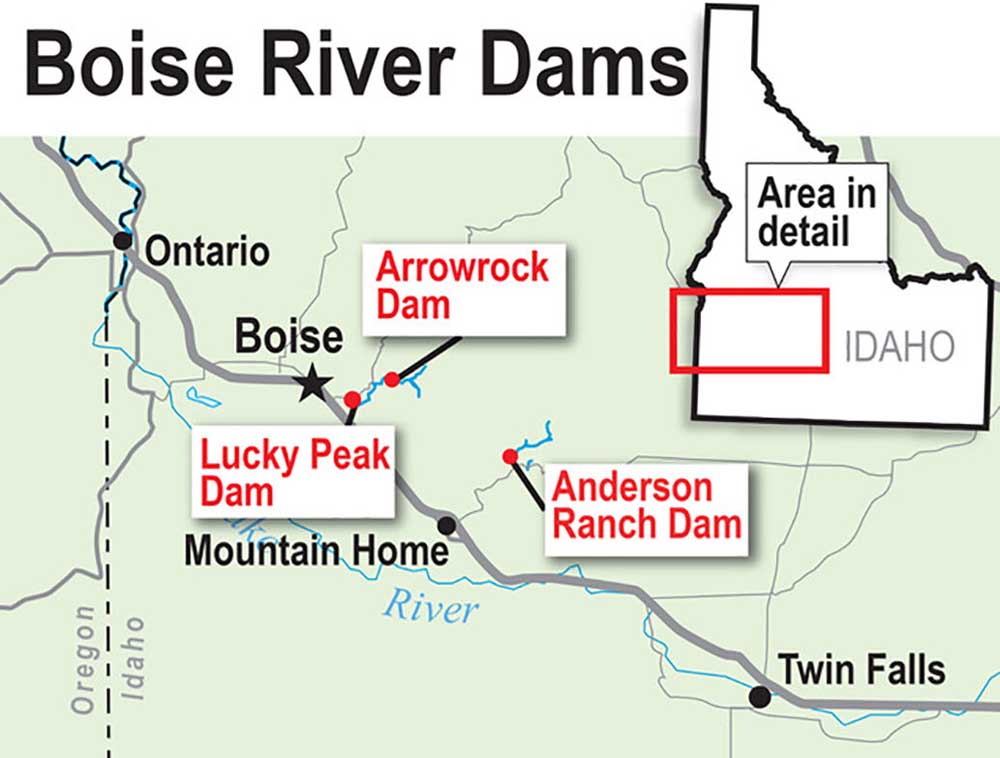

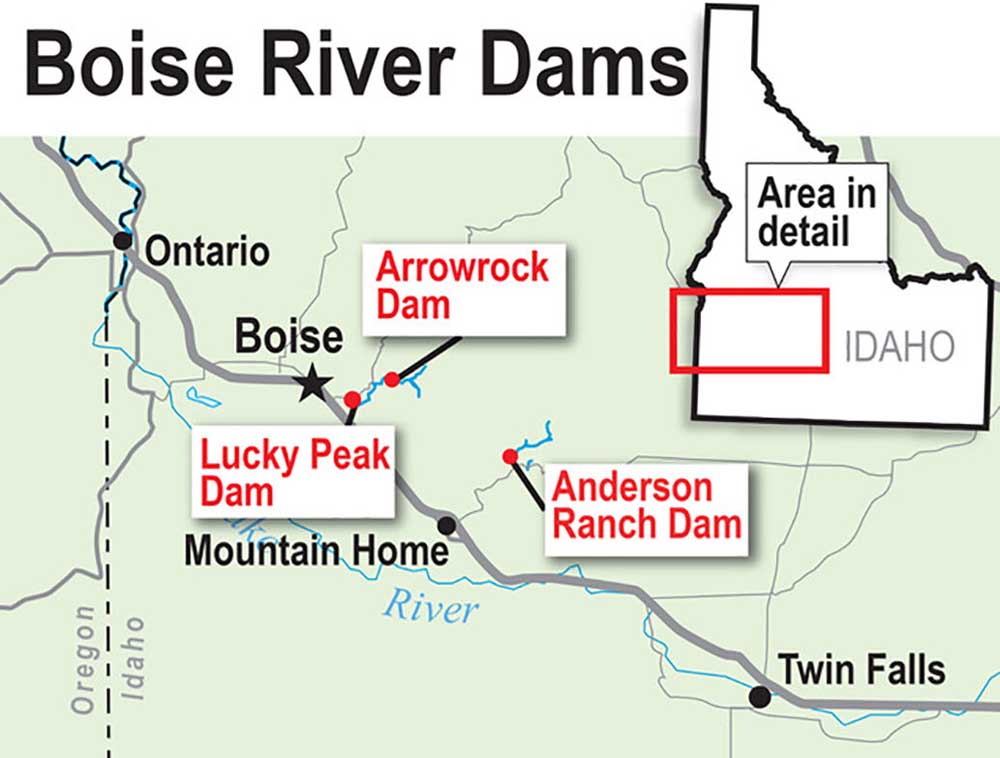

- Three dams Idaho

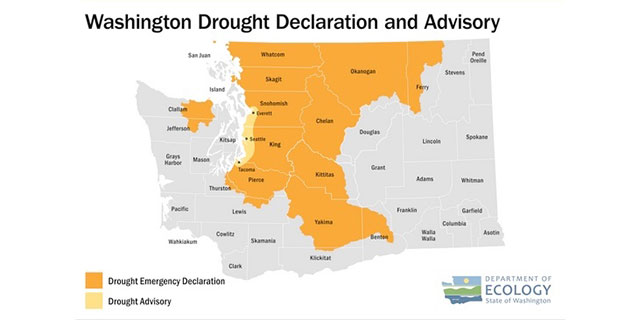

- Climate Prediction Center winter forecast

STAR, Idaho — Rex Barrie viewed the Boise River as it crawled under the bridge that straddles it near Star, Idaho.

It was Oct. 1 — the first day of the new water year — and Barrie, the Boise River’s watermaster, was inspecting diversions that feed water to irrigators.

“As the season winds up, demand is less,” Barrie said. “So we can reduce flows and keep water in the reservoirs.”

Doing that will be crucial to next year’s irrigation season. For the Boise River — and rivers like it around the West — 2022 could be a make-or-break year for irrigated agriculture. This year’s drought and high heat left most of the region’s rivers and reservoirs running low, and farmers have their fingers crossed that the winter will bring a lot of rain and a hefty snowpack in the mountains that will replenish them through next summer.

The Boise River is fed by three major reservoirs — Anderson Ranch, Arrowrock and Lucky Peak. All of them had above-average volumes of water stored at the start of this year’s irrigation season. But drought-fueled demand from farmers quickly used the water supply, prompting several irrigation districts and canal companies to halt water deliveries about a month early.

About 325,000 irrigated acres lie downstream from the three reservoirs.

“Water users are going to be watching winter precipitation very closely to make some sort of plan going into the 2022 water year,” Barrie said.

As of Sept. 30 the reservoirs were at 24% of capacity, 11 percentage points below what is typically required for the system to fill if the mountain snowpack is average.

“What we really need is an above-average snowpack this year to get us back to where we are going to get a good runoff and get the system filled,” Barrie said.

La Nina to the rescue

The massive drought that has dogged much of the Northwest and California appears to be on the verge of breaking. An unusually wet October and a La Nina weather pattern offer hope for the new water year. Already this month, a procession of storms has rolled in from the Pacific Ocean bringing rain to the lowlands and snow to the mountains.

La Nina’s lower sea-surface temperatures typically drive wetter, cooler conditions to the Northwest while it tends to leave California drier, particularly in the south.

To get the region back to normal, the rain and snow will have to keep coming, forecasters say.

Double-whammy

The drought presents a double-whammy for farmers. Not only does the amount of irrigation water shrink, but so does the amount of water in the soil. Last year’s dry fall and spring quickened snowpack runoff, but much of it went into the thirsty soil instead of streams and reservoirs. That in turn prompted more irrigation demand through the growing season.

Troy Lindquist, a National Weather Service hydrologist in Boise, said last winter’s snowpack was below normal in many Idaho basins, and the usual spring rains “didn’t really materialize.”

But the outlook for this winter sparks optimism, he said. The NOAA Climate Prediction Center winter outlook favors above-normal precipitation, mainly due to La Nina. That includes “just about all of Idaho, especially across the northern half of the state.”

Erin Whorton, water supply specialist at the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service in Boise, said October’s above-average precipitation is encouraging.

“We have really dry soils and low reservoirs, but the recent precipitation is helping with the soil-moisture issues we’ve been having,” she said. “A lack of soil moisture was a huge issue last year.”

Good fall precipitation helps make the soil runoff-ready come spring, Whorton said.

Soil moisture is improving, “but we have a long way to go to get back to conditions agricultural producers would like to see,” she said. “The ideal is to go into winter and have really wet soils. They freeze, and moisture is preserved throughout the winter.”

Lacking last year’s above-average storage in southern Idaho and southeastern Oregon reservoirs, “we need to make up a lot more, with above-average snowpack and more precipitation,” Whorton said.

Irrigation makes West bloom

Agriculture was hurt by high heat and drought in the West, where farming is a big business.

The 2017 Census of Agriculture found that the total market value of agricultural products sold that year exceeded $45.1 billion in California, $9.6 billion in Washington, $7.5 million in Idaho and $5 billion in Oregon.

And irrigation makes the region bloom. In California, more than 7.8 million acres are irrigated — more than 31% of the state’s farmland.

Idaho’s irrigated acreage accounts for nearly 3.4 million acres, or 29% of total farmland.

Oregon has 1.66 million irrigated acres, a little more than 10% of the 15.96 million total acres. Washington irrigates 1.69 million acres, about 11.5% of the nearly 14.68 million total acres.

‘Spring drought’

Scott Oviatt, the snow survey supervisory hydrologist at the Natural Resources Conservation Service in Oregon, said snow last spring melted out two to three weeks earlier than normal at most of the state’s mountain measurement sites. That was followed by “a spring drought that continued essentially from March 1.”

Snow telemetry sites recorded their lowest or second-lowest totals ever, he said.

“And as a result, streamflows across the state in many locations are at record lows,” he said in late September. Reservoir storage is also very low, particularly east of the Cascade Range.

“The concern is that if we do not receive adequate fall precipitation before snow accumulation season, we will certainly have deficits going into next year,” Oviatt said.

Dry soil and low streamflows would mean there is a good chance the drought will become multi-year, he said.

However, the outlook is “dynamic and developing,” hinging on fall and winter precipitation such as the October storms that have consistently drenched the region.

Scott Pattee, the NRCS water supply specialist in Washington state, said if a good snowpack materializes, as forecast, its benefits will be highest if fall and spring conditions are near normal.

Reservoir operators rely on spring rains to reduce irrigation usage, “and that didn’t happen this year,” he said.

“Before we get into winter, wetting up our soils until the snow comes is really the key to starting a good water year,” Pattee said.

California is getting rain, snow

While the Northwest is looking forward to a wet, cool winter courtesy of La Nina, California’s outlook leaves a bit less room for optimism. La Nina precipitation often misses much of California and the Southwest.

As of Oct. 19, all of California was in at least a moderate drought, the U.S. Drought Monitor reported. Since the monitor started in 2000, the state’s longest drought has stretched from December 2011 to March 2019. California had another prolonged drought in 2007-09, according to the state Department of Water Resources.

Greg Norris, the NRCS state conservation engineer, said California just emerged from its second straight water year of below-average rainfall.

Regions vary, he said, “but the state as a whole was far below average in both rainfall precipitation and snowpack.”

He said Shasta and Oroville are the state’s two main reservoirs that collect runoff from rainfall and snowmelt, and “they are both currently between 35% and 40% of normal storage for this time of year. These low lake levels translate to low or nil water allocations to water districts and farmers.”

The reservoirs have dropped more in each successive dry year, compounding water availability problems, Norris said.

If there is any remaining surface water this fall, “the farmers will definitely use that to increase moisture in the root zone for permanent crops such as trees or vines,” he said. Otherwise, groundwater will have to be used.

“Depending on the amount and timing of precipitation and snowfall, it is possible for reservoirs and soil moisture to recover in a year, as seen in 2017,” he said. But that “was an extremely wet year, setting records in some areas.”

Help may have already arrived. October precipitation for the new water year has been above average as far south as San Luis Obispo. A huge storm last weekend hit much of the state with record rainfall and heavy snow at high elevations in the Sierra Nevada. Flooding was reported in the San Francisco Bay Area, and Sacramento had a record 5.4 inches of rain in a day.

Norris described the Oct. 24 storm as “very unusual.” It brought “extreme” rainfall to a swath of the state that included the Bay Area, Lower Sacramento Valley, northern San Joaquin Valley and central Sierras.

As of Monday, Lake Oroville had gained 139,445 acre-feet of water since Oct. 18, according to the state Department of Water Resources. Lake Shasta had gained 18,893 acre-feet.

Farmer’s view

Josh Norris, who custom farms in addition to running his own operation in southwest Idaho, said it’s yet to be determined if the drought will force farmers will change their crop lineups and percentages next year.

“The consensus of what I’ve heard is ‘Wait and see,’” he said.

That may well sum up the situation across the West.