Soilborne wheat mosaic virus spreading in Washington

Published 10:45 am Thursday, May 18, 2023

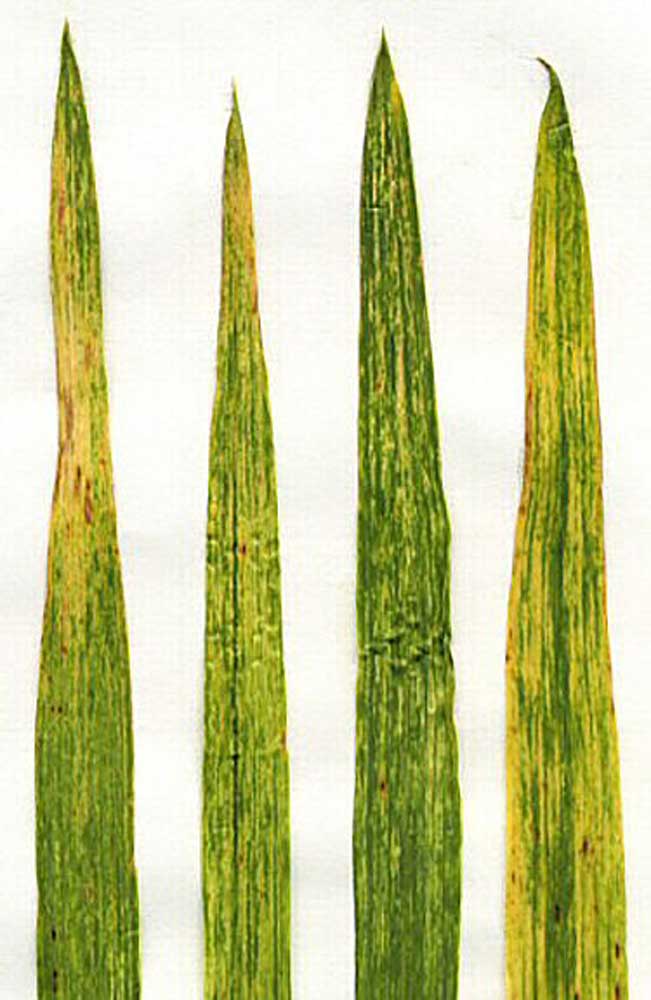

- Foliage of a wheat plant infected by soilborne wheat mosaic virus.

Soilborne wheat mosaic virus, commonly found in the Walla Walla area, has been identified about 100 miles away near Ephrata, according to Washington State University researchers.

Winter wheat from an irrigated field was submitted to WSU’s plant diagnostic clinic in late April with symptoms of virus infection. The field was described as having “random patches of affected wheat with no pattern,” according to WSU’s Small Grains website.

Wheat within the patches was stunted, with older leaves that were yellowish with purple tips. The newer leaves had lighter yellowish blotches.

“This is not a disease to take lightly,” said Tim Murray, WSU Extension plant pathologist.

It’s transmitted by a fungus-like organism that lives on the roots of different plants without causing damage.

“Any time soil moves, if it’s from a field that’s infested, then this pathogen could move,” Murray said. “It could move on equipment that is moved between fields, on automobile tires, on soil on shoes.”

Soilborne wheat mosaic virus was first introduced into the U.S. in the Midwest following World War I on contaminated equipment, Murray said. The disease has spread around the country.

“Historically, it has tended to make long jumps that we don’t fully understand,” Murray said.

It was found in the Willamette Valley in about 1995, northeastern Oregon about 10 years later, and Walla Walla in 2007. It was confirmed in new locations in Washington and north Idaho last year.

Researchers haven’t found a clear link between the most recent sightings, Murray said. The fields in central Washington are irrigated, and fields in Walla Walla and Idaho are dryland.

A soilborne pathogen typically takes a while to build up before it’s severe enough to be recognized, he said. Yellowish spots can be attributed to other causes.

Infection occurs in the fall after planting, but symptoms don’t show up until late winter or early spring.

“The other thing that’s confusing about it: As the temperatures warm up, the plants appear to recover,” Murray said. “They green up and they do grow, but they’re not healthy. The damage is still going to persist in these spots where the disease occurred.”

Yield loss compared to healthy plants ranges from 5% to 30%.

WSU advises farmers to look for unusual spots in their wheat fields, and plant wheat varieties with good resistance to the disease.

“… This hasn’t been a problem that breeders in the region have been actively breeding for,” Murray said.

Breeders in the Great Plains, Midwest and Northeast do breed for resistance to the virus. When Northwest breeders use germplasm from those areas, “they can accidentally carry along these resistance genes that we don’t know are there until we get the right circumstances.”

When WSU researchers compared varieties in a highly infested field near Hermiston, Ore., a resistant variety yielded 150 bushels and a susceptible variety yielded 45 bushels.

That’s a farmer’s only option, Murray said. Soil fumigation and crop rotation won’t work.

“This organism that transmits the virus is very long-lived in soil,” he said. “Basically, once a field is infested, it’s infested for the duration. It’s just a matter of learning how to manage it.”

WSU includes information about resistance in its variety trial data. Growers should submit a sample to WSU’s diagnostic clinic if they suspect plants have the virus.