As gravel removal debate grinds on, Washington farmers lose ground

Published 3:00 am Thursday, January 24, 2019

- Satsop River erosion

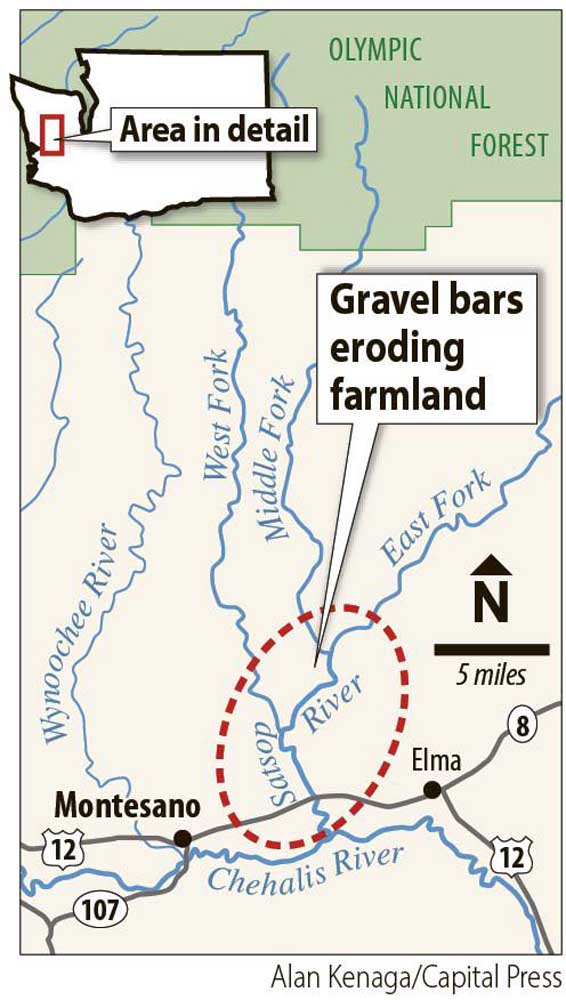

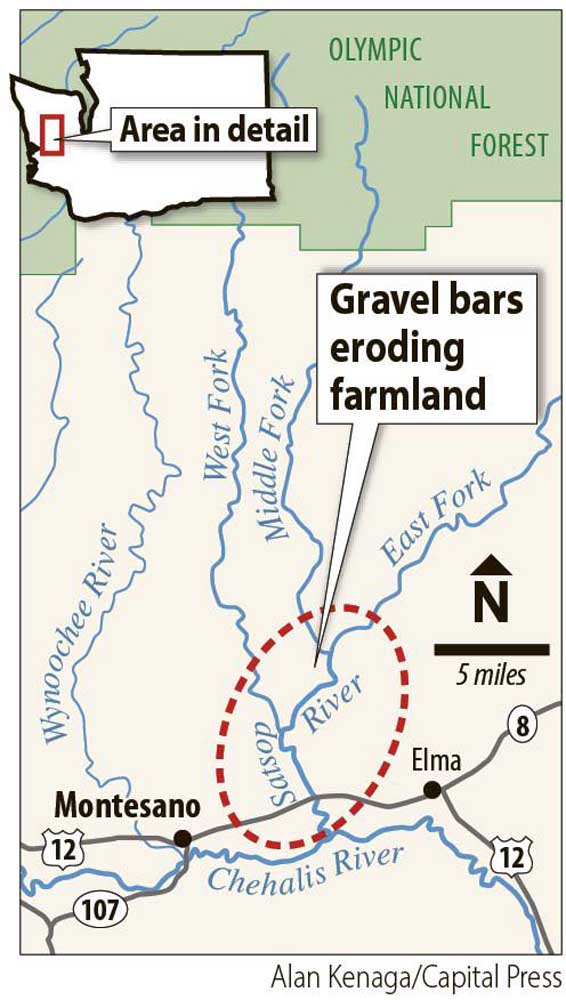

MONTESANO, Wash. — This winter, farmer Steve Willis has watched the Satsop River in Western Washington wash away what last summer was a field of corn.

The cause: Gravel washing down from the Olympic Mountains continues to pile up on one side of the channel and deflects the current. The redirected river then erodes farmland that the Willis family has farmed since 1925.

The massive erosion has been a problem for years, but this year it’s been so bad it urgently needs to be fixed, one conservation district official says.

Willis said he wants to remove some of the gravel and give the water room to flow past, not through, his farmland. Others — state agencies, environmental groups and tribes — are generally cool to the idea of removing any gravel. They worry it could hurt the salmon that spawn upriver.

At the moment, there is no solid plan to stop the Satsop from sweeping more of his farmland downriver.

‘Frustrating’

“It’s so frustrating,” Willis said. “I’ve had many sleepless nights over this.”

Willis and his neighbors are among the Western Washington landowners who see their fields in floodplains erode. The rivers are changing for several reasons, said Brian Cochrane, habitat and monitoring coordinator of the Washington State Conservation Commission.

“We now have a shift in the frequency and size of events, which means you’re going to see erosion where you haven’t seen it before,” he said. Rain running off hard surfaces and more winter precipitation falling as rain instead of snow are likely contributing to the higher rivers.

In an effort to halt the massive erosion, state lawmakers have introduced bills based on the premise that in some places rivers are eroding the valuable land because too much gravel has accumulated.

Sponsoring lawmakers have proposed “pilot projects” to show that removing gravel need not harm salmon. State agencies have been, at best, lukewarm, toward the idea. Environmental groups and Native American tribes have been opposed, and the bills have failed.

“What I’m running into is that the environmental community just hates it,” said Sen. Steve Hobbs, a Snohomish County Democrat who sponsored bills in 2014 and 2015 that proposed pilot projects, including some in Whatcom and Snohomish counties, as well as on the Satsop River in Grays Harbor County.

Hobbs said he battled the assumption that he wanted to return to a time when some riverbeds were damaged by gravel mining.

“The perception is that what was done in the past is what I want to do now,” he said. “The image of a backhoe throwing out gravel — I have to find a way to get rid of that image.”

Gravel was mined from the Satsop River for decades, probably to the point that more was taken out than was replenished, according to a 1989 study by university geologists and funded by the Washington Department of Ecology and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Willis said gravel mining was phased out beginning in the 1980s, and since then the gravel bars have continued to grow.

The river has changed course, ripping out trees and plants before it gets to farmland, he said. “There’s tons of dirt going down the river,” he said. “I don’t see any benefit in what’s happened to the fisheries.”

Farmland disappears

The loss of land is impressive. Terry Willis, who is married to Steve’s cousin, Greg Willis, is a former Grays Harbor County commissioner and past president of the Grays Harbor-Pacific County Farm Bureau. She said they placed their manufactured home three-quarters of a mile from the river in 1980. The river is now less than 100 feet away.

“We’ve let a (gravel) bar that didn’t exist 10 years ago destroy farmland that’s existed for hundreds of years,” she said.

The erosion has put farms and ranches that grow hay, corn and pumpkins and raise dairy and beef cattle at risk, according to a report compiled by an engineering firm. No one has surveyed the amount of farmland lost, but the report notes the river has moved up to 100 feet in a year in some places and has caused the loss of “tens of acres” of productive farmland. Steve Willis figures he’s been losing about an acre a year.

Terry Willis said government agencies are concerned about the erosion and are working on multi-part responses, but they need a push from legislators to seriously consider gravel-bar maintenance.

Removing gravel would require the approval of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the state Department of Fish and Wildlife, Department of Ecology, Department of Natural Resources and Grays Harbor County.

“You have to kick it up to the Legislature,” Terry Willis said. “As far as I’m concerned, it needs to come from the top down.”

The Washington State Dairy Federation has made the same argument.

The federation’s executive director, Dan Wood, told lawmakers five years ago that gravel was displacing water and that while collaboration on long-range, basin-wide flood-control plans was fine, landowners needed immediate help that the bureaucracy wasn’t delivering.

“We have talked this to death for decades,” Wood told the Senate Agriculture Committee. “We are losing farmland now. We’re having homes flooded now. We need to move from discussion to action.”

Nothing has changed since then.

‘Geared for inaction’

“For whatever reasons, agencies are geared for inaction more than action,” Wood said this month. “This is a no-brainer to me.”

The Washington Legislature convened Jan. 14 for its 2019 session. Orcas and their need for more salmon will be a top priority, and environmental lobbyist Bruce Wishart said he expects that will stiffen opposition to gravel removal. “This is not the time to be rolling back protection for salmon,” he said.

On behalf of the Sierra Club, Wishart has testified against bills that included removing gravel from the Satsop River as a pilot project. Such projects could endanger salmon habitat and water quality without fixing whatever upstream land uses are sending down sediment, he said.

Also, rivers are reverting to their natural state, he said. “If you live in a floodplain, you have to understand the river moves.”

Pros and cons

The Nature Conservancy helps plan projects that seek to let rivers flow naturally while preserving farmland. The organization’s Washington Coast Community Relations Manager Garrett Dalan said gravel removal should neither be quickly embraced nor quickly discarded by planners.

“The pros and cons of something like gravel mining should be weighed at the project level,” he said.

Washington Department of Ecology shorelines manager Gordon White said the agency supports trying to redirect the Satsop River away from the Willis property. “Ecology wants to do something to support the preservation of farmland there,” he said.

On the larger issue of removing gravel to reduce erosion and flooding, “we think there’s no one formula on that,” White said. “We think it’s best not to have a blanket ‘yes’ or ‘no.’”

Many government agencies are involved in trying to develop a plan to stop the Satsop River from eroding farmland. No one federal, state or local agency appears to have the final responsibility.

“Bureaucracies, just by design, are risk-averse,” said Scott Boettcher, staff to the Chehalis River Basin Flood Authority.

Three counties and several cities formed the flood authority after widespread flooding in 2007 in the Chehalis River Basin. The Satsop River drains into the Chehalis River.

Boettcher said the basin would be a “great testing ground” to try gravel removal “with a tremendous amount of oversight.”

“I think to be bold, we need legislative action,” he said.

This year, logs and rocks may be tied together and placed on the riverbank. The idea is the river would embed the logs and rocks into the dirt and shore up the bank. At this time, however, there is no money, permits or plan for doing that.

Gravel removal

Gravel removal is not part of any short- or long-term tentative plan.

“The basic reason is removing gravel is not easily permitted,” said Grays Harbor Conservation District watershed restoration program manager Tom Kollasch. “We’re trying to work in the realm of possibility.

“The way we’re managing rivers has changed. I know that’s frustrating to Steve,” he said. “We understand what he’s saying.

“They are losing tons of good farmland,” Kollasch said. “Steve is right. There is a lot of gravel at the lower end.”

Besides damaging fish habitat, other objections to removing gravel include concerns that taking out rocks will speed river flows and make them more destructive. Another objection is that gravel will have to be removed repeatedly and still won’t fix upriver and downriver flooding problems.

“We’re trying to build a plan that looks at the river at a broader level,” Kollasch said.

House Agriculture and Natural Resources Committee Chairman Brian Blake has toured the erosion-prone stretch of the Satsop River. It’s in his district.

“We’ve got a bunch of competing interests, and I haven’t heard a good short-term solution yet,” said Blake, D-Aberdeen. “I’m supportive of gravel management. We could certainly try again.”

Hobbs, the legislator from Snohomish County, said he introduced bills because a constituent was losing his land. “It was so sad to hear it,” he said.

Hobbs said he “burned up so much political capital” trying to get his bills passed. The last time he tried, he got the Department of Fish and Wildlife to support it, and the bill passed the Senate.

“I thought I was going to win,” he said. Then he ran into “a giant brick wall” of opposition from environmental groups.

“There are some sad stories, and I can’t get any movement.”

So he has left the matter alone for a couple of years.

“You know, if I can get some grass-roots support going, I wouldn’t mind doing it again,” he said. “Maybe we should try again.”